Let’s face it, centenaries are not as rare as they appear at a glance. Sure enough, they only happen once, and only exactly one-hundred years after an event, but if we’re being honest with each other, every day could be a centenary of something. It’s just usually not something interesting.

Well, this Sunday, the 28th of October, 2018, is going to be a centenary of something interesting, I can guarantee that.

It was a hundred years ago that the Republic of Czechoslovakia split from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and gained independence.

Prague is going to be chock full of commemorations, demonstrations, wreath-laying-ations, and you’re more than welcome to enjoy all that. But every time there is a big anniversary happening, it’s a great idea to not just get lost in the present, but to look back at the event we’re celebrating.

A Nation Without a Country

To talk of independent country of the Czech and Slovak peoples, to understand why it would mean so much to us, it’s good to look way back in history and realise for just how long we lived under somebody else’s rule.

The last proper Czech ruler recognised internationally was 700 years earlier, King Wenceslas III. After his murder and the end of the Přemyslid dynasty, there were the Luxembourgs, Jagiellonians, and Habsburgs. We did try, between the Luxembourgs and the Jagiellonians, to have our own king again, but his Protestant faith left the country somewhat isolated.

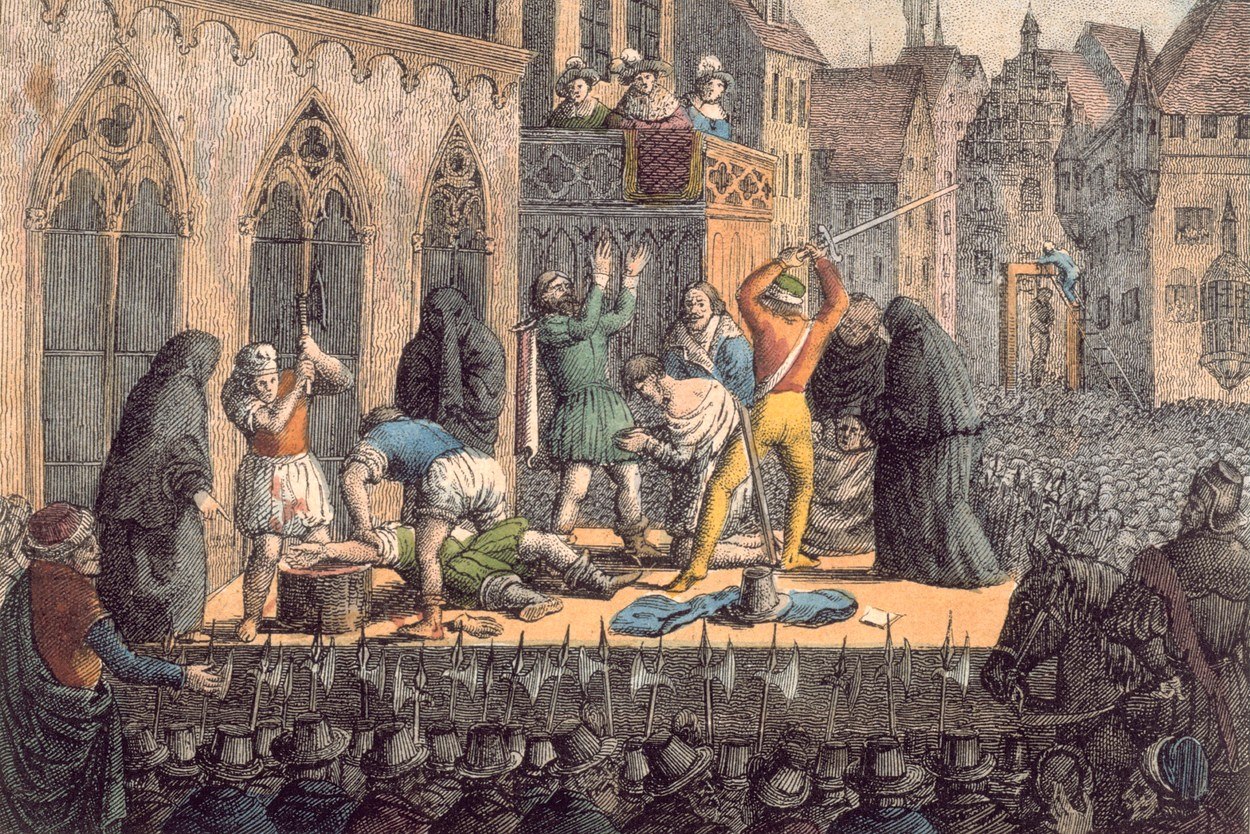

The Habsburgs took over the throne of Bohemia in 1526 and remained strongly in control of the country for the next nearly 400 years. We did rise up against their rule in the beginning of the 17th century, but the uprising was quickly crushed, and any kind of patriotic fervour had to wait.

Waking Up a Nation

It was in the 19th century that the idea of “being Czech” started to gain momentum. A series of linguists, historians, writers, and politicians became loosely affiliated in the Czech National Revival (“Národní Obrození” in Czech). The language was restored from a marginalised language of the poor, to a living language capable of the highest art. With it came a cultural boom, and soon an upsurge in patriotic sentiments. The Slovak people were developing along similar lines.

But the Austrian (and since 1867 Austro-Hungarian) authorities were unwilling to allow the increasingly vocal Czechs to establish autonomy. After all, if the Czechs got more freedom, what about the other nations? The slippery slope could break the Empire apart.

The gradual process of political negotiations and reforms was abruptly silenced in July of 1914. Can’t have seditious talk in a state of war! But as it often happens, the more you try to suppress something, the more the pressure builds, just waiting for the right opportunity to release.

During the First World War

When the war broke out, the Czech people found themselves in a difficult position. Some felt loyal to the Emperor, some saw an opportunity to change things more than they ever thought possible. Most, however, were simply subjects who had to obey orders.

We’re not even sure, but as many as 1.4 million men were drafted into the Austrian army, of whom between 140,000 and 300,000 died.

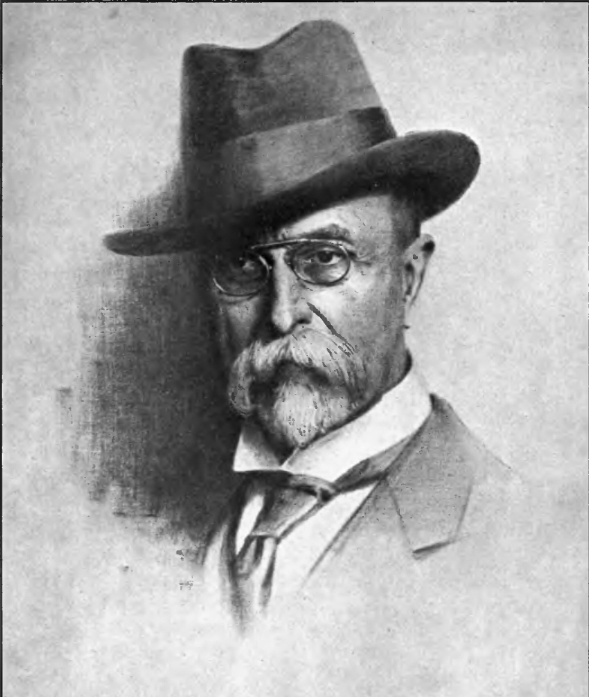

At a time like that, talk of “Czech independence” or “autonomy” was considered high treason. In fact, many were arrested, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk had an arrest warrant issued against him and Karel Kramář was sentenced to death, although he was later given an amnesty.

The situation during the war started to become more and more desperate. The war effort drained the country, and Bohemia, because of its traditional focus on industry over agriculture, soon started suffering major shortages of food. At a time of crisis, people were looking for solutions. Leaving an already unpopular empire embroiled in a war we didn’t care for seemed more appealing than ever.

But how do you break free of something that you’d been a part of for almost 400 years?

Stronger Together

The idea sounds simple on paper. If Austria-Hungary were to lose the war, and if the Czech people were to end up on the winning side, well, winner takes it all, right? Now just how to get there…

Firstly, we knew we couldn’t get there alone. According to a 1921 census, there were 6.8 million Czechs and 3.1 million Germans (back then we didn’t differentiate between Germans and Austrians). And many of the Germans were not keen on the idea of a country ruled by the Czechs. Similarly, there was a large Hungarian minority in Slovakia. To get a stronger majority, we decided to join forces under the banner of “Czechoslovakism”. Thus, we had about 8.8 million Czechoslovaks.

Our ideas lined up well with the Allies, who were eager to break up the Austro-Hungarian Empire to limit its ambitions going forward. Breaking it up along national lines seemed like the perfect solution. Already in 1915, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk delivered a memorandum called Independent Bohemia to London and a speech asking for Czechoslovak independence in Geneva. This is why the warrant for his arrest was issued, and why he remained in exile for the duration of the war.

The war of 1914 revealed […] that Austria-Hungary is unable to protect and to administer Bohemia and the other nations. Vienna has utterly failed in this war […].

Bohemia must now take care of herself.

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk: Independent Bohemia, 1915

Walking the Walk

Talking about independence was one thing, but the Allies were not going to help us out simply out of the goodness of their hearts. If they were to give us a country of our own, we were going to have to earn it.

There were many Czechoslovaks who were willing to pick up arms and help the Allies fight. They started joining up and forming military units, now called the Czechoslovak Legions (Československé legie). By the end of the war there were about 140,000 volunteers in Legions primarily in Russia, France, and Italy.

Some were volunteering ex-patriots, but many were captured soldiers who originally fought on the Austrian side, while many more deserted outright. This made them traitors from the Austrian point of view, and if captured, they faced the prospect of an execution.

Their successes on the western and eastern fronts helped strengthen our diplomatic position. After all, not only were we asking for something, but we were actively helping to the best of our abilities.

The Third Most Famous Woody

By the beginning of 1918, things were not going well for Austria-Hungary. Emperor Franz Josef was dead, the economy could hardly bear the strain of war, and when the United States of America joined the war in 1917, things looked dire.

Leveraging the weakened position of Austria, Czechoslovak politicians published the “Three Kings Declaration” (Tříkrálová deklarace, named after the Christian holiday of the Three Kings on January 6th). In it, they demanded autonomy for the Czech and Slovak peoples within Austria-Hungary.

This feeling was bolstered by one of the three most famous Woodys, behind Woody Woodpecker and Cowboy Woody, President Woodrow Wilson of the USA. His Fourteen Points, published on January 8th, demanded autonomous development for the nations under Austro-Hungarian rule.

In May, representatives of the Czech and Slovak peoples signed the Pittsburgh Agreement, where they said they would work together towards an independent Czechoslovakia.

Declaring Independence

Austria-Hungary was trying to bring the war to a diplomatic end, and to that effect, Emperor Charles I promised to reform his country, and federalise it to improve the status of different minority nations.

Czechoslovak representatives, however, felt this was a ploy to get the war to an end and to then try to preserve the status quo. They felt that it was akin to a drowning man grasping at straws, but they were not taking any chances.

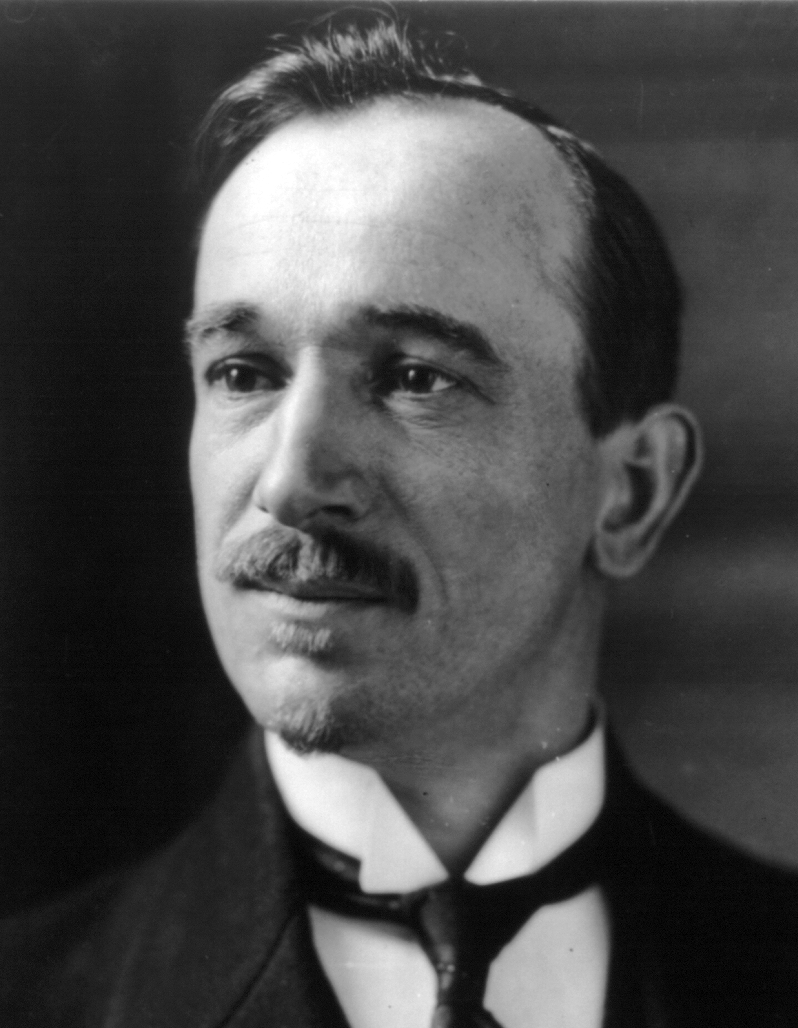

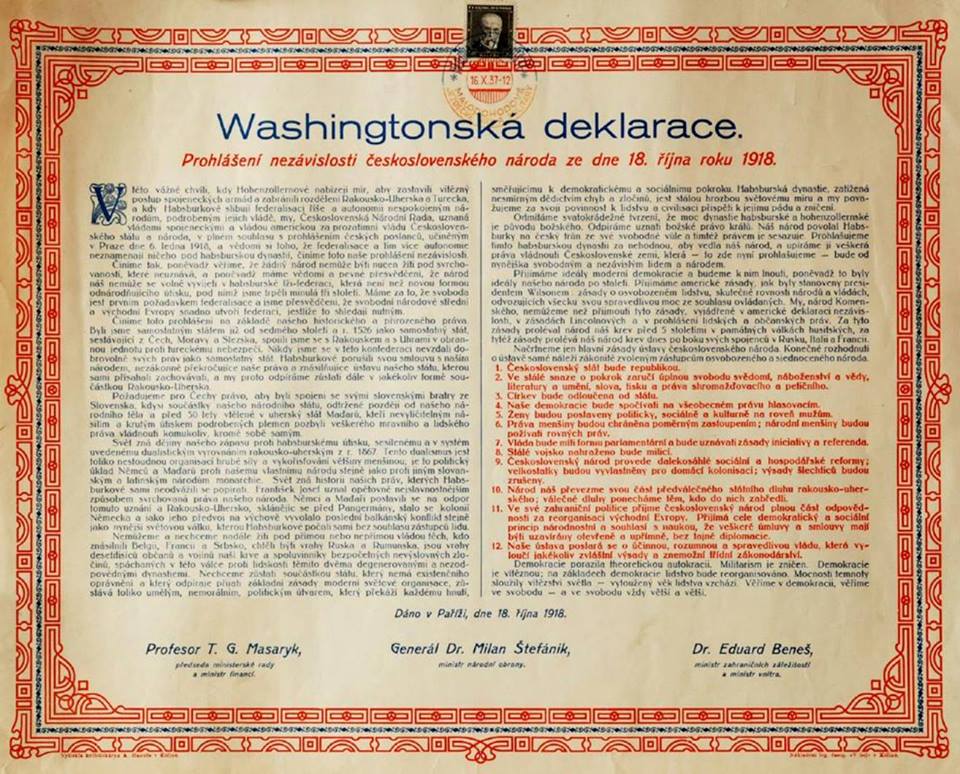

In reaction, they published the Washington Declaration on the 18th of October. Officially known as the Declaration of Independence of the Czechoslovak Nation, its signatories, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, Milan Rastislav Štefánik, and Edvard Beneš reject any Austrian proposals of autonomy, instead choosing independence. They reject theocratic autocracy and divine right of kings, instead choosing liberty and democracy.

Our nation elected the Hapsburgs to the throne of Bohemia of its own free will, and by the same right deposes them. We hereby declare the Hapsburg dynasty unworthy of leading our nation, and deny all of their claims to rule in the Czechoslovak Land, which we here and now declare shall henceforth be a free and independent people and nation.

Washington Declaration, 1918

Now we had to make it official back home.

The 28th of October 1918

In the morning of the 28th of October, 1918, a delegation of the National Committee led by Karel Kramář (soon to be prime minister) met up with Edvard Beneš (soon to be foreign minister) and agreed that the newly formed country would be a republic, and that Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk will become the president.

News started spreading about events a week ago, when Austria-Hungary accepted the terms of peace at the end of the First World War, with one of those terms being that it will recognise the autonomy of the people of Czechoslovakia.

With that bit of news, people around the city of Prague started to feel that autonomy and independence are really one and the same, and spontaneous gatherings cropped up everywhere. Naturally, one of the biggest happened in the main square of the New Town, Wenceslas Square.

It was there, around 11 a.m., that a priest called Isidor Zahradník addressed the people.

“We are free. Here, on the steps of the memorial of the Czech Duke Saint Wenceslas, we swear that we wish to become worthy of this freedom, that we will defend it with our lives.”

Isidor Zahradník, Wenceslas Square, 28th of October 2018

He then continued, accompanied by a cheering crowd, to the nearby train station, back then bearing the name of Emperor Franz Josef. Two months later it would be named after President Woodrow Wilson, and today its name is a lot duller “Main Train Station”. It was there that he telegraphed the news of the establishing of Czechoslovakia to the world.

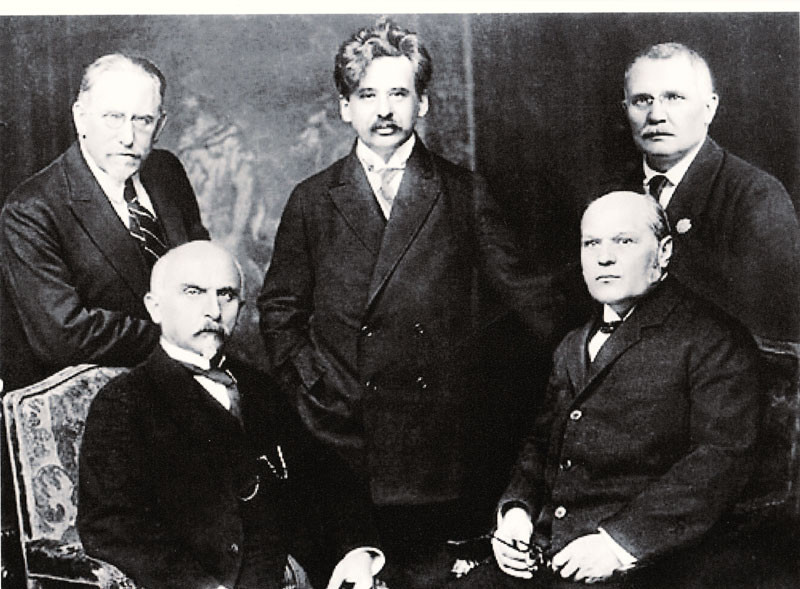

Not wanting to be left out, the whole declaration was repeated an hour later, in the same place, by the statue of Saint Wenceslas, by a group of men now called the “Men of the 28th of October”.

Those five men, Antonín Švehla, Alois Rašín, Jiří Stříbrný, Vavro Šrobár and František Soukup, signed a new law later that day: The Law to Establish the Independent State of Czechoslovakia.

An independent state of Czechoslovakia has come into life.

Law to Establish the Independent State of Czechoslovakia, 1918

100 Years Later

A lot has happened since the 28th of October 1918. There have been good times, and there have been bad times. But through it all there still is a sovereign, independent country of the Czech people. Oh, and the Slovak people have a country, too!

There’s so much more to talk about. The Foreign Legions and the two years it took them to return from the Eastern Front, because they got caught up in a civil war there. The attitudes of the Slovaks towards Czechoslovakia, the broken promises of autonomy and the strife it caused. The country-defining people like Masaryk, Beneš, Štefánik and more.

This is a part of history I will be coming back to. And no wonder – it is a part of history that a hundred years on still has the power to make us stop and reflect.